REVIEW: Inabakumori - Anticyclone

Underage vocaloids and grown men: degenerate robot music or disarming insights into childhood anxiety?

48:41 // November 17th, 2019 // U&R

Vocaloid is a tough sell with a niche Western following — and unsurprisingly so. For the unacquainted, the lowdown here is a synthetic voice, modelled on specifically recorded samples from human singers but programmed as midi to voice any lyrics with a range of possible timbre modifications. This software typically comes attached to a luridly marketed, tightly licensed anime avatar (vocaloid being of course a primarily Japanese phenom), and its instrumentals tend to take its synthetic qualities in their stride with ultra-digital production stylings and hyperactive arrangements. If you ever get a chance to hear a proper karaoke freak take a shot at a vocaloid track in the flesh, you get a good grip on the edge of your seat and hold on for all that's dear.

The upshot is overstimulating and at times frankly exhausting, but beyond that, I doubt I'm alone in instinctively associating vocaloid with something sinister and distinctly male auteur-shaped: popular vocaloids are almost exclusively female whereas the vast majority of their frontrunner producers are men writing first-person lyrics for mouthpieces explicitly aged as minors (Hatsune Miku at 16, Kagamine Rin at 14). It's a more complex story than projected male fantasies or unchecked indulgence—many of the most recognisable and reputable faces in contemporary J-Pop have their roots in vocaloid (Yoasobi, Kenshi Yonezu, Ado, REOL), while the vocaloid fanbase boasts 50:50 gender parity (not to be confused with the ~80% male V-tuber fanbase!)—and yet, even the most tasteless or unsavoury content I've sampled from J-Pop's cracked-out underbelly was underscored by some indication of earnest expression or willing participation. Vocaloid's uncanny girl-puppetry is thornier to reckon with.

Take Inabakumori and our present case study, his 2019 debut Anticyclone: if you're perturbed by the thought of a male producer, in his mid-20s at the time, using a synthetic voice derived from an elementary school girl to fuel jagged indie rock stormers with distinctly mature perspectives on social awkwardness, emotional turmoil and faltering self-expression, then you simply have your head screwed on right. And yet, there's more than meets the eye here; if Inabakumori is one of many cases where vocaloid invites critical scrutiny, there are several respects in which his take on the form can also reward it (beyond the fact that he sees off a number of indecently well-constructed pop songs).

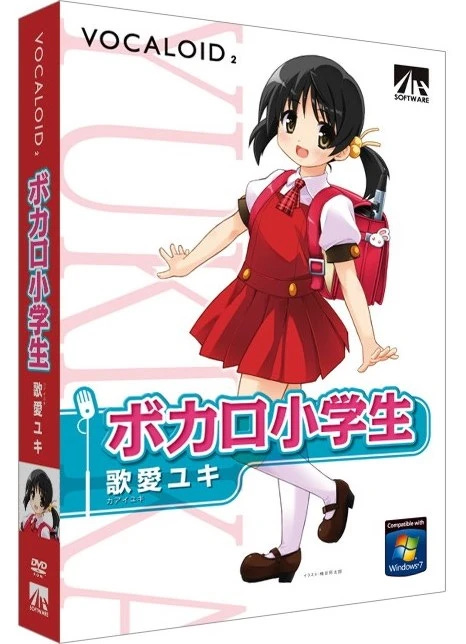

Let's start with the vocaloid herself. Inabakumori is unusual among vocaloid producers in that he primarily uses Kaai Yuki, who in turn is unique among vocaloids in that her source recordings were provided by a nine-year-old girl and her mascot-character (licensed and designed by the same studio that programmed her) is explicitly of elementary school age. If this immediately screams recipe for disaster, rest assured that Inabakumori's lyrics are not sexual (although many points state or imply a male addressee and the narrator of some tracks is preoccupied by her failure to declare or navigate romantic feelings), and the vocaloid community has shown encouraging rigour in policing the use of Kaai Yuki for perceivably sexualised material. No need to fear the worst, as many caught the wrong side of the Japanese language barrier routinely do.

The 'creepiness' here is more insidious, partially for aesthetic reasons—it's inherently discomforting to hear the facsimile of a small child asphyxiating herself over phrasings few adult lungs could sustain—but also through Anticyclone's lyrics, as we will soon see. However, in both cases the effect stems from how Inabakumori treats Kaai Yuki's childishness as dislocated and unnatural. He has specifically credited her for a cool demeanour disproportionate to her age, and his music is full of touches that play against her archetype, rather than indulging it for moe kitsch. We hear this best on "Loop Spinner" (#5), a hysterical slew of gymnastic hookwork that summersaults right over the bar of pop ecstasy. It takes until the first chorus for the 'loop' in question is shown to be the same circuitous pish constantly piped into every radio victim's headphones, promises of reciprocated romance, unending gratification et al.:

好きって言葉

saying "I love you":

くるくるくる回るその言葉

round and round and round, those words fly

唇介して思い果たそう

from my lips to bring the feeling to life

繰り繰り繰り返す

again and again and again,

音 リズム メロディは

cuz the sound, the rhythm, the melody

色褪せないから

are never gonna fadeSo far, so insubstantial (and so dangerously close to the media the IRL Kaai Yukis of the world are asked to consume indiscriminately). Take her sentiment at face value and it's practically nauseating — but make it to the bridge, and she reciprocates this nausea , replacing those perfunctory I love yous with a far more desperate declaration, her cipher of schoolgirl cliches exhausted and laid bare:

どうやってループを止めるの?

How do I stop the loop?

後れる少女思想

My girlish mentality can't keep up

こどものまま歳を数えていく

I count the years as they pass, but I stay a childThis image of thankless limbo suggests at least a baseline of self-awareness — one cannot imagine Inabakumori charting a hellscape of dysphoric Peter Pan-isms without tacitly acknowledging himself as the architect. Rather than indulge in Kaai Yuki's apparent childishness, he frames it as a curse, a source of neurotic discomfort; if he programs her as a ditsy lovebot for the first chorus, he then goes on to makes her suffer for it and, in turn, disgusts us with the promise of any gratification that giddy initial sweetness might have held (the scuzzy chromatic riff that opens the track is a tell here, as is Kaai Yuki's vertiginous delivery of the chorus).

This is not the last we’ll see of reflexive undertones of faulty programming or scenarios innately hostile to Kaai Yuki's robot-girl platform. The late highlight "Utsushi Asobi" (Copy And Pastime, #11) puts her in a bind familiar to many portrayals of emergent AI and/or lived childhoods: overcompensating for poor social skills and articulation by imitating second hand speech. In this case, she aims to reproduce her addressee's written words with tracing paper:

なぞっていけ なぞっていけ

Tracing and copying, tracing and copying

きみの言葉になれなかった、

I couldn't match your words,

あたしの真っ新にひとつ滲んだ言葉は

the single, smudged word on my empty page

疲れ果て もう見る影もないな

is faded, you can't even make it out now

その通りにしただけだったのに…

and yet I just did it like you…

あたしは間違ってよかったのに。

and yet I'd have been better off making my own mistakes.As the song's girl-persona strives fruitlessly to find her own voice, Inabakumori further victimises her relationship with language through the phrasing demanded by his lyrics. While several of the album's hooks rely on Kaai Yuki's failure to deliver anything approaching naturalistic diction—see her helium explosions in "Tsukurikake no Shinshou" (An Image in the Making, #7) or her slurred delivery throughout "Lost Umbrella" (#2)—none of these are quite so unsettling or compelling as "Utsushi Asobi"'s chorus: a full asthma attack's worth of contorted breathing, weird pitch jumps, and quavering extended vowels that sound at constant risk of choking themselves to silence. Keenly aware of Kaai Yuki's capacity for mangled enunciation, Inabakumori turns her unrealistic delivery into a grotesque parallel to the self-expression her persona yearns for — Kaai Yuki cannot achieve the tonality to imitate an authentic flesh-and-blood schoolgirl, who in turn cannot find the words to speak for herself, and both parties are ultimately disguises for Inabakumori himself. Absolutely no one achieves unfiltered self-expression in this track's rituals of imitation and pretence.

Meanwhile, "Namida Denpa" (Tears Radar, #6) maps human receptivity to love and interconnection over the precarious faculties of tech — unreliable ‘emotional wavelengths’ are hardly an original or controversial metaphor (Utada Hikaru said it best!), but this one takes on an extra layer given that the mouthpiece is herself a precarious faculty of tech. The narrator's distress at not feeling understood by her addressee culminates in one of the album's most memorably warped images:

零れる劣等感とドキドキ心音の狭間に

Jam your headphone jack into the space between

イヤフォンジャックを突き刺して

my pounding heartbeat and my uncontainable inferiority complexThis image evokes J.G. Ballard’s manglings of errant human desires with technology and is violent enough that the narration seems to stall and we are forced to view it for authorship rather than character. The plea is practically a direct address from Inabakumori himself, scene-setter and disruptor of wavelengths that he is — he leaves us in no doubt whatsoever over the volatile, anxiety-ridden nature of his product, and yet he asks us to tune in all the same. Do so and you'll be ‘rewarded’ with further violence in the song's climax, this time aesthetic: a barrage of flat-handed piano chords and snares, both played in merciless straight eighths, both flaunting their artificial VST trappings in their brutally constant dynamics, impossible to imagine from a human performer. He hits us with what Kaai Yuki has been struggling to get off her chest all this time: a dizzying fit of stimulation, overwhelmingly intense to the point of dissociation, brought about by wilful abuse of technology. Just as he slyly nudges us closer to identifying with Kaai Yuki, she takes on a more serene, intelligible tone than at any other point of the album. After all, it's we, not her, who are in the line of fire for this particular panic attack — all hell has broken loose, and she barely has to hum over it!

One of the album's most resounding highlights practically reads as a satire of a core anime trope (or, less charitably, as a knowing embrace of the same qualities it espouses): the Kaai Yuki of "Cooler Girl" (#4) is an appropriately icy exaggeration of the implacably nonchalant kuudere girl. Her characterisation here stems from a familiar standoffish mystique…

好きも嫌いも別にいらない

I don't care whether you like or dislike me

見透かして、なんて言える立場じゃないわ

it's not my place to expect you to know what's on my mind…but draws her chronic frostiness to cartoonish extremes, gleefully poking a few toes over the border of body horror:

感情の使用量省エネしたい、したいの

I wanna save the energy I use on emotions

まだあったまった空気吐き出せないのよ

I still can't blow out any warm air

寒いままだね

in this cold stateEven more than "Loop Spinner"'s nauseous entertainment machine, "Cooler Girl" is perhaps the most cogent metaphor for Inabakumori's approach to Kaai Yuki: as a superlatively passive 'agent', she demands rigorous engagement to articulate anything at all, and the more he stress-tests her, the more disturbing and evocative her feats of endurance become. As on "Utsushi Asobi" (Copy and Pastime) and "Namida Denpa" (Tears Radar), Anticyclone's aesthetic peaks emerge where he drops his most unashamed computerised fuckery on her, and its most enduring character standpoints find ample synergy here. The narrator of "Cooler Girl"'s sardonic declarations are nothing if not under duress. One thinks again of Ballard, and finding in his vision of authorship something eerily pertinent to Inabakumori’s clinical acts of sadism:

We live in a world ruled by fictions of every kind […] The fiction is already there. The writer’s task is to invent the reality […] in a sense, the writer knows nothing any longer [...] He offers the reader the contents of his own head, a set of options and imaginative alternatives. His role is that of the scientist, whether on safari or in his laboratory, faced with an unknown terrain or subject. All he can do is devise various hypotheses and test them against the facts.

J.G. Ballard - Introduction to Crash (1995)All of which offers a new perspective on the duality of Kaai Yuki the schoolgirl character vs. Kaai Yuki the software tool: the latter enables Inabakumori to exploit aesthetics that would never be set before a real nine-year-old, and yet in doing so, and without resorting to anything crass or lewd, he is able to serve up a vision of anxiety, emotional disjuncture, social disconnection and faltering self-expression with a level of complexity seldom afforded to media portrayals of children, all through the inner monologue of a virtual character painfully aware, as so many real kids are, of how much she struggles to speak for herself. Whether or not it's 'true' to the character or biography of Kaai Yuki is besides the point — she is a fiction invented to be reinvented in consumer hands (and sell merchandise along the way), and this plasticity provides a morbid converse for the impressionable frames of real children, who, needless to say, would be a good deal less resilient to the psychological and physiological demands of Anticyclone's performances.

The most censorious hawks may well argue that, virtual surrogate and PG rating be damned, this still amounts to little more than torture porn, all the worse for Inabakumori's selective humanisation of his puppet. Or, put from the perspective of vocaloid’s more gung-ho proponents, where's the fun to be had in vocaloid if you deny yourself the kick of hearing the robot girl used as a crash test dummy for whacked-out digipop? I see the case here, and yet it's no less valid to be suspicious of male producer-songwriters using elastic girl-robots to indulge their every whim than it is patently absurd to expect them to treat their software as actual human equals. Kaai Yuki is not a child (though her childlike image rightly demands similar safeguards): she is a hyperbolic cipher for neuroses experienced in particular by children and young adults, as is Inabakumori's real focus in characterisation. On an abstract level, her childlike frame functions as a metaphor for the powerlessness one feels even as an adult upon experiencing the fits of anxiety or emotional disconnect she charts; on a more literal level, that image puts us in the uncomfortable position of having to question how many of those neuroses we can identify in actual childhoods.

All of which is to say that the initial ick Inabakumori provokes is a necessary reaction, courted by his work directly and repurposed with something approaching artistic merit. However, I'm not credulous enough to assume his entire standpoint has a subversive focus, and it is by no means perfectly realised even when that is what he reaches for. "Sakasama Shoujokan" (Sakasama Girl Feeling, #12) is a glaring offender here, a snapshot of an otome protagonist repulsed by her undeclared romantic feelings. Inabakumori puts a dark spin on narrator's inner turmoil and self-doubt, miring them in transgressive overtones that I care for not one bit:

これはダメだ いけない好きだ

This is no good, this is a wrong love

おとな過ぎると気付いているんだ

I get that it's too much of an adult thingHe's at least wily enough to turn this back on his audience and raise an eyebrow at their own potentially complicit desires….

あたしの好きであなたの好きが

If my affection is turning your affection

おかしくなってしまう時代なら

into something warped and inappropriate

もう散々なんで どういなくなれば

then it's all messed up — how can I get out of here?…but the song remains a distasteful blip for a tracklist that otherwise does good work carving disturbing impressions out of superficially wholesome themes, not to mention that its subtext of a mutually corrupting consumer-performer relationship is something he has already charted with far more taste and dexterity on "Loop Spinner". "Sakasama Shoujokan" (#12) scans as all the more gratuitous as such.

Leaving aside Anticyclone's adult/child, male/female, man/machine tensions to focus entirely on the *arthritic air quotes* music, it's both to this record's credit and detriment that its torqued-out rush does not let up in the slightest. At its best, it's impossible to conceive of Inabakumori's pop ecstasy beyond the stiflingly artificial confines in which we encounter it (we’ve seen examples aplenty on that front!), but good luck distinguishing meaningful differences between these tracks on first listen. Anticyclone's bombardment is simply too much for a full 14 tracks on a runtime just shy of 50 minutes. Its maximalism makes it an unnecessarily laborious digest, something that would be handily amended on Inabakumori's 2022 follow-up Weather Station.

If there's a clean takeaway to be had in this swamp of robotic girltears and tongue-tied youthfulness, it's that vocaloid's disposition for male-engineered sadism needn't be an indulgent dead end (Bandcamp Daily very conveniently published a feature yesterday on how vocaloid serves the needs of a wider range of artists). I am not nearly invested enough in vocaloid as a whole to posit Inabakumori as an exception that proves or disproves any kind of rule, but if he wilfully exploits Kaai Yuki's image of innocent girlhood, then he thereby crafts a bracing set of portrayals of emotionally sensitive topics that pertain to children but are rarely extended to their perspectives. Add the aesthetic extremities of her robotic voicings, and the upshot is a unique take on overstimulated stress relief; it should come as no surprise that the vocaloid target audience of middle/high-school otakus have found themselves squarely in sync with this. Beyond that cohort and anyone partial to this brand of high octane indie pop, it's obvious enough that this music will never claim universal appeal, but you'd have to be an incorrigible cynic not to see the scope for nuanced performance: adults writing as children, boys dressing up as virtual robot-girls — what would Shakespeare do with vocaloid? Don't call me.

7/10

Further listening:

gimme this but streamlined -> Inabakumori - Weather Station

make it human and wholesome -> ZUTOMAYO – Hisohisobanashi

stop apologising for degeneracy -> Kikuo - Kikuo Miku 7

do real people sing like that lol -> Soutaisei Riron - Hi-Fi Anatomia

giving hugh the ability to add images to reviews is either the best or worst thing to have happened to music criticism ever

jk, excellent stuff, much to consider, many thoughts

As someone who has no real interest in or knowledge of vocaloid music, this was an incredibly interesting read and I loved every second of it. I did check out one track and was pleasantly surprised so I may try listening to the rest of it.